Displaying results 251 - 260 of 1072

Artificial Intelligence, Medicine, Bias, and Ethics

Artificial Intelligence, Medicine, Bias, and Ethics

Speed That Kills – Platforms, Democratic Expression and the Role of Universities

Speed That Kills – Platforms, Democratic Expression and the Role of Universities

Inspiring our reflection on Technology & Ethics

As technological breakthroughs continue to push the boundaries of what is possible in the 21st century, the Pierre Elliott Trudeau Foundation’s 2020 Scholars, Fellows and Mentors are examining ethical challenges and issues around how we might benefit from technology while mitigating any of its ethical risks in our individual and collective lives.

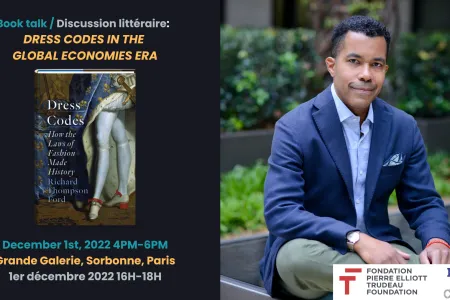

"Dress Codes: How the Laws of Fashion Made History" by Richard T. Ford

Richard Thompson Ford's book "Dress Codes: How the Laws of Fashion Made History"

Je suis les économies mondiales / I am the Global Economies

Un poème collaboratif de Barbara Grantham, Michelle Liu, Jean-Frédéric Morin et Alexandre Petitclerc, au nom de la 20e cohorte de la Fondation Pierre Elliott Trudeau / A collaborative poem by Barbara Grantham, Michelle Liu, Jean-Frédéric Morin, and Alexandre Petitclerc, on behalf of the 20th cohort of the Pierre Elliott Trudeau Foundation